In an effort to better identify the underlying causes of the disproportionately large firefighter retirement costs facing many of Rhode Island's cities and towns, WatchdogRI.org decided to conduct an in-depth analysis of the firefighter contract and pension provisions within one particular community. We chose the Town of Johnston, because its firefighter pension plan has one of the largest unfunded pension liabilities per taxpayer in the state, and we wanted to find out how it got this way. In other words, to understand the pensions, you first have to understand the contract.

Using Rhode Island's open records law, we requested a full set of career payroll records for four randomly chosen firefighters. We asked for the most recently retired, 5th most recently retired, 10th most recently retired and 15th most recently retired firefighters' payroll records and information about their pension and COLA payments. Johnston has two pension plans for firefighters: a municipally-run plan for all firefighters hired before 7/1/1999 and the state-run MERS plan for those hired after 7/1/1999. Based on data we received in December of 2014, Johnston has roughly 30 members of an 87 member force who have yet to retire under the municipally-run pension plan. We learned that it's this municipally-run firefighter pension plan, "Pension Plan A", that has one of the largest per capita unfunded firefighter pension liabilities in the whole state, with a liability of more than $55 million. As we dug into the contract, certain themes emerged.

A primary theme in the Johnston contract is a repeating monetization of certain contract elements – or put another way, double or triple dipping in the same benefit provision. Take for example, unused sick days. First, as an incentive, in any given year that a firefighter does not use sick days he receives a cash bonus for a portion of each unused sick day. Second, upon retirement, a cash bonus is given converting accumulated sick days into the current salary rate at retirement. And third…the cash value of unused sick days can be rolled into the calculation for determining the firefighter's base pension amount. That means his last year's salary is artificially inflated with accumulated sick pay. There are several examples of double dipping of certain contract elements, which include longevity bonuses, clothing allowances and vacation days, in addition to sick days.

Of all of the Rhode Island firefighter contracts that we reviewed, Johnston's municipally-run pension has by far one of the most generous formulas for determining the starting pension amount for a firefighter.

The main components of the formula are:

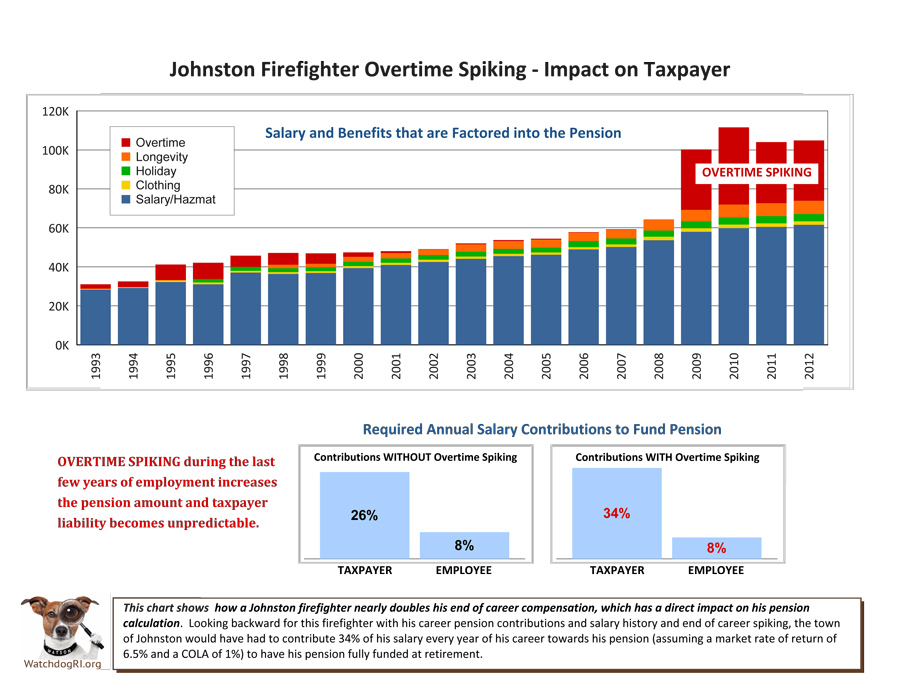

The fact that overtime and accrued sick and vacation days are in the pension calculation caused us to worry about 'pension spiking'. Pension spiking occurs when a starting pension amount is inflated due to increases in compensation that occur in the last few years of an employee's career. Spiking leads to an inability to accurately save for an employee's retirement. In Johnston's case, we have data from one employee who worked almost no overtime in his entire career until the last three years, when his overall salary nearly doubled with the overtime compensation. As a result, although he was contributing a contractually required 8% of salary a year towards the pension, in effect he put in much less than 8% on a career basis because of the last three year's large increase in compensation.

Assuming a 6.5% market rate of return on pension investments and a 1% COLA, the Town of Johnston would need to have paid in 34% of this employee's pay every year of his career to fully fund his pension on retirement. At a 7.5% rate of return and .5% COLA the Town share would be 26.7% of this employee's pay.

Of course, early on in this employee's career no one can predict how many overtime hours may or may not be worked at the end of this employee's career – making this scheme not only financially reckless and impossible to plan for but also guaranteeing that the employee contributions to the pension are short changed relative to the final pension benefit.

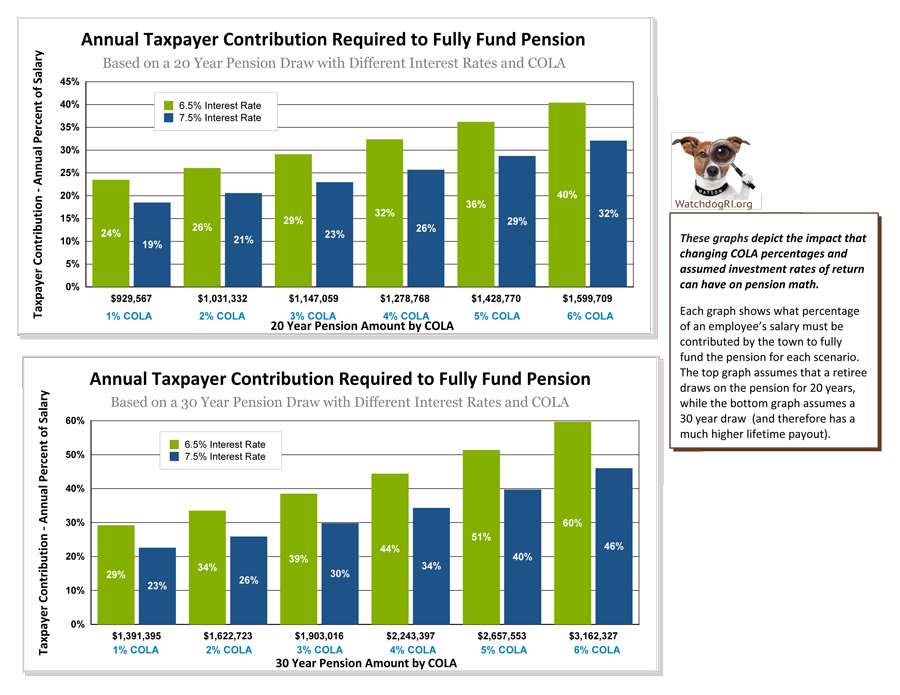

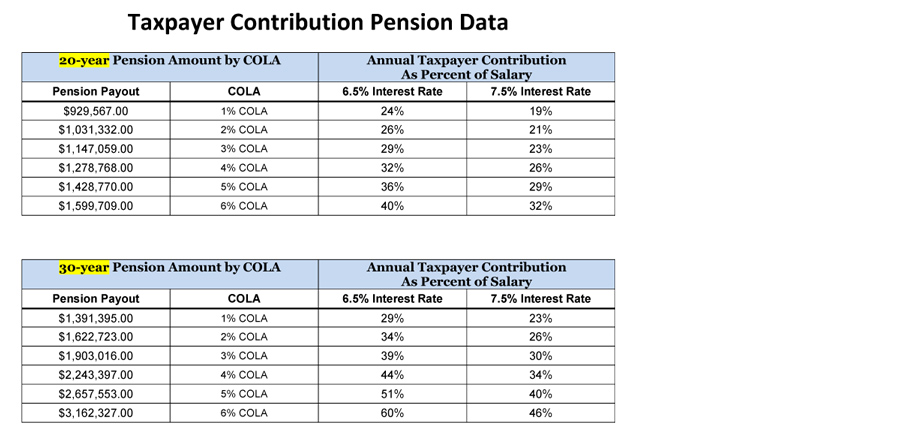

Town contribution rates of 30% to 40% to fully fund unbalanced pension schemes like Johnston's are wholly unsustainable. In fact, historically, many towns have not made consistent and appropriate pension contributions, making a seriously bad problem much worse. This is the 'kick the can down the road' phenomenon, where all sides choose to pretend that the pension funding problem does not exist and choose to let the issue fester and burden future generations of both retirees and taxpayers.

Johnston's firefighters are able to collect nearly as much – and in some cases more – in annual pension payments the first year they retire than they received in their last year of salary. This is an unsustainable and recklessly engineered scheme that endangers the financial futures of retired firefighters and the finances of the town.

The fact that Johnston has moved newer employees into the MERS retirement system with a very different pension formula is a financially positive step, but the 30 or so firefighters still to retire under the plan described above means that future Johnston taxpayers will be paying this bill for many years to come.

The retirement generosity of Johnston's firefighter contract does not end with the pension plan.

In what we have found to be unique to Johnston, retired firefighters continue to receive a longevity bonus once they retire, which is paid in an annual lump sum payment from the Town outside of the pension system.

Longevity bonuses were conceived as a reward to keep veteran employees in the department. Longevity bonuses are used in most municipal and state contracts, but in no other firefighting contract have we found the concept of paying longevity bonuses post-retirement.

Johnston is in effect not only paying a pension to their retired firefighters – they are also paying them an incentive bonus to stay alive.

What can be done?

To a very large extent, little can be changed with contracts like Johnston's firefighter contract outside of bankruptcy. Current elected leaders often were not the negotiators of the financially reckless clauses found in these contracts – they are often just left needing to figure out how to pay for them. The employees bargained in good faith for the benefits, so they are usually unwilling to give them up.

Changes to firefighters' contracts in Rhode Island usually end up being arbitrated in a process called 'binding arbitration'. In exchange for not being able to strike, firefighters can bring contract disputes to an arbitrator for resolution.

Binding arbitration is a flawed process in Rhode Island. The flaw lies in the arbitrator selection process. Both sides have an opportunity to reject certain arbitrators – almost all of whom reside out of state. What can and does happen is if an arbitrator makes a decision that angers one fire union, that arbitrator may not get a chance to arbitrate for any other fire union for quite a long time. This places a financial penalty on the arbitrator – and potentially skews the arbitration process. Rhode Island should reconsider how the process of selecting an arbitrator is performed for binding arbitration.

There are many Rhode Island laws that place mandates, boundaries and limits on a town's ability to manage fire protection services. What is missing is a legal framework protecting taxpayers from out-of-balance contract provisions like those found in the Johnston firefighter contract. It is unreasonable to obligate taxpayers to fund employee pensions at a cost of as much as 40% of salary. A fiscal stability 'circuit-breaker' is necessary that would make illegal any pension scheme that required taxpayer funding beyond a reasonable percentage of salary.

With the financial instability that too many Rhode Island towns suffer from, this kind of override mechanism is needed from the General Assembly to overcome what in some cases is many decades of poor fiscal decision making. Everyone loses when towns cannot meet their financial obligations – let's make sure those obligations are rooted in fiscal sanity.